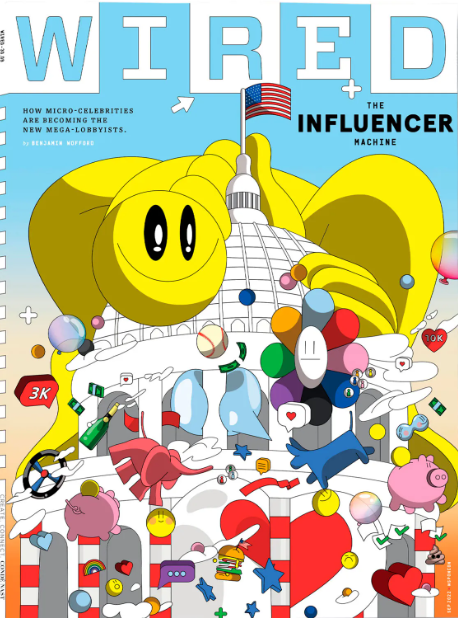

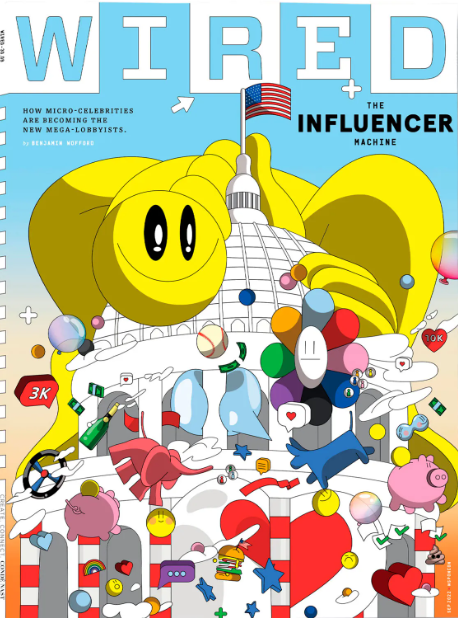

The Carbon Underground | WIRED | September 2022

Sometime after the dinosaurs died, sediment started pouring into the Gulf of Mexico. Hour after hour the rivers brought it in—sand from the infant Rockies, the mucky stuff of ecosystems. Year after year the layers of sand hardened into strata of sandstone, pushed down ever deeper into the terrestrial pressure cooker. Slowly, over ages, the fossil matter inside the rock simmered into fossil fuels.

And then, one day in early 1901, an oil well in East Texas pierced a layer of rock more than 1,000 feet below Spindletop Hill, and the well let forth a gooey black Jurassic gusher, and the gusher began the bonanza that triggered the land rush that launched the age of petroleum.

One of the products of the economy that black gold built is the city of Port Arthur, Texas. Perched on the muggy shores of Sabine Lake, just across the border from Louisiana, it’s among the global oil-and-gas industry’s crucial nodes. Port Arthur is home to the largest petroleum refinery in North America, opened the year after the Spindletop gusher and now owned by the state oil company of Saudi Arabia. The area emits more carbon dioxide from large facilities every year than metropolitan Los Angeles but has a population 3 percent the size. Smokestacks are its tallest structures; nothing else comes close. Around town, pipeline pumping stations jut up from shopping-center parking lots, steam from petrochemical plants hisses along highways, and refineries flank both sides of main roads, their ductwork forming tunnels over traffic. Janis Joplin, who grew up here, described it in a 1970 ballad called “Ego Rock” as “the worst place that I’ve ever found.”

Tip Meckel has a more hopeful view of the place, maybe because he spends so much time looking down. A lanky research scientist at the University of Texas’ Bureau of Economic Geology, Meckel has worked for most of the past decade and a half to map a roughly 300-mile-wide arc of the Gulf Coast from Corpus Christi, Texas, through Port Arthur to Lake Charles, Louisiana. Though he’s the grandson of a refinery worker and the son of an oil consultant, his interest isn’t in extracting more petroleum from this rock. Instead, he has devoted most of his career to figuring out how to turn it into a commercial dump for CO2.

The idea is that major emitters will hoover up their own carbon waste, then pay to have it compressed into liquid and injected back down, safely and permanently, into the same sorts of rocks it came from—carbon capture and sequestration on a scale unprecedented around the globe, large enough to put a real dent in climate change. Suddenly, amid surging global concern about the climate crisis, some of the biggest names in the petroleum industry are jumping in.

Read more here.

Burned | Fortune | October/November 2021

Six years ago, Liz Babb and her husband, Angelo Aloisio, retired financial services executives and new empty nesters, sold their place in San Francisco and moved to the woods. They bought a 1970s house on a steep slope in Portola Valley, an enclave of forested canyons minutes from Silicon Valley’s center that boasts a bohemian history, a reputation for moneyed discretion, and jaw-dropping views. It was an iconic—if, by local standards, modest—northern California dream home: wood construction, picture windows, multiple decks, and, everywhere, trees.

Lush vegetation blanketed the property: oaks, redwoods, and all manner of shrubs and bushes. They enveloped the house, but not only that. Soaring through the center of the structure—rising from the dirt, through the first-level floor, up three stories, and out the roof—stood a massive oak, its trunk encased by interior glass and its branches and leaves canopied over the house. “We were ready for our rural adventure,” said Babb, an avid hiker. When she first saw the shelter-magazine-worthy aerie, she recalled, “I fell in love with it.”

In August 2020, love turned to fear. A lightning storm struck hills stretching between Portola Valley and the Pacific Ocean—hills, that, like much of California and the West, are parched from years of drought. The bolts set the hills aflame. By the time five weeks later that firefighters extinguished what had come to be called the CZU Lightning Complex fires, the inferno had scorched some 86,500 acres and destroyed about 1,500 buildings. The blaze came within about eight miles of Portola Valley. The smoke plume turned the skies above the town a putrid, pallid orange. More permanently, the fire altered Babb’s view of her world. The ecology “has changed,” she said. “We’re a tinderbox here.”

Last November, fear turned to fatalism. Babb got a letter from Safeco, the company that had insured her homes for more than 15 years. Safeco informed her it was going to drop her homeowners policy in January; it had concluded her house in the trees was too severe a fire risk. For the next several weeks, Babb searched for another insurer, but other carriers, too, saw her house as a firetrap. Finally, days before their policy was to expire, she signed up for the California FAIR Plan, a last-resort fire-insurance pool that California established following urban riots in Los Angeles in the 1960s for people unable to get coverage through the regular market. Still, she will pay $8,000 annually for her full complement of homeowners insurance, about $7,000 of it for fire. That’s four times what she paid a year ago.

Babb and Aloisio, like many of their neighbors, can afford the expense. But even their rarefied ZIP code offers a window into the economic fallout from wildfires—recurring disasters that are intensifying in part owing to climate change. Here as elsewhere in California and across the American West, a surge of decisions by insurers not to renew the fire policies of property owners in combustible locations is spurring political fights and stoking fears of sinking property values. More consequentially, it is exacerbating societal inequities in ways that foreshadow dilemmas that will become more common in a warming world.

Read more here.

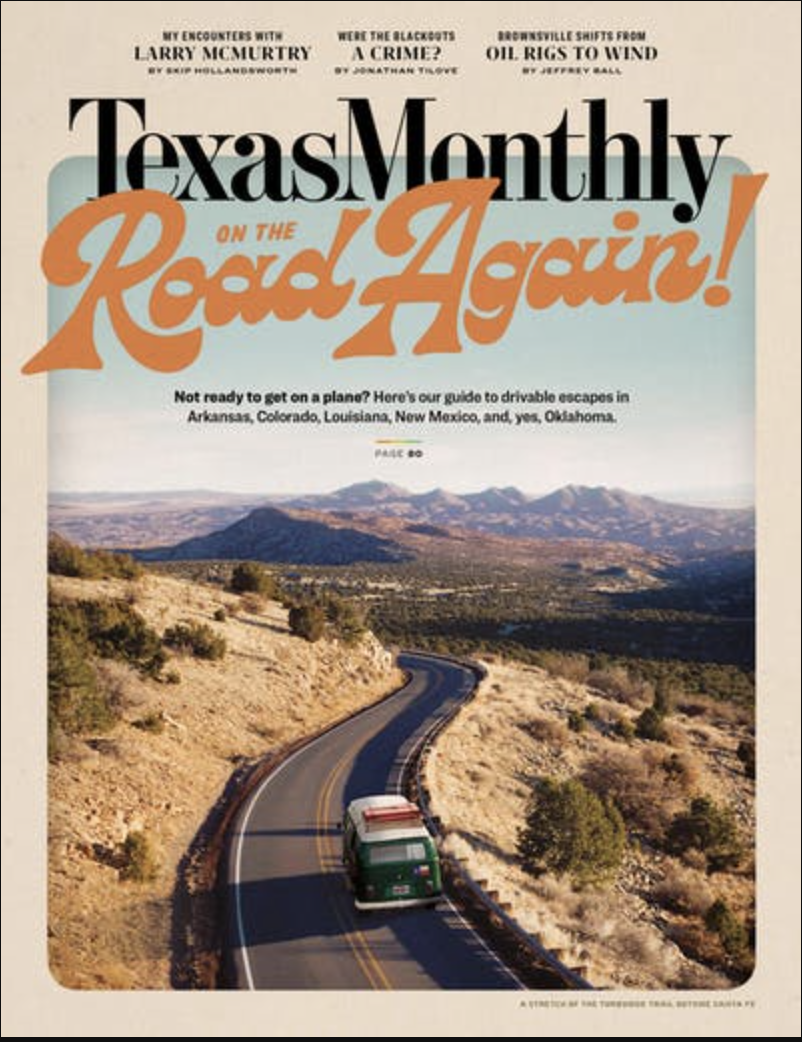

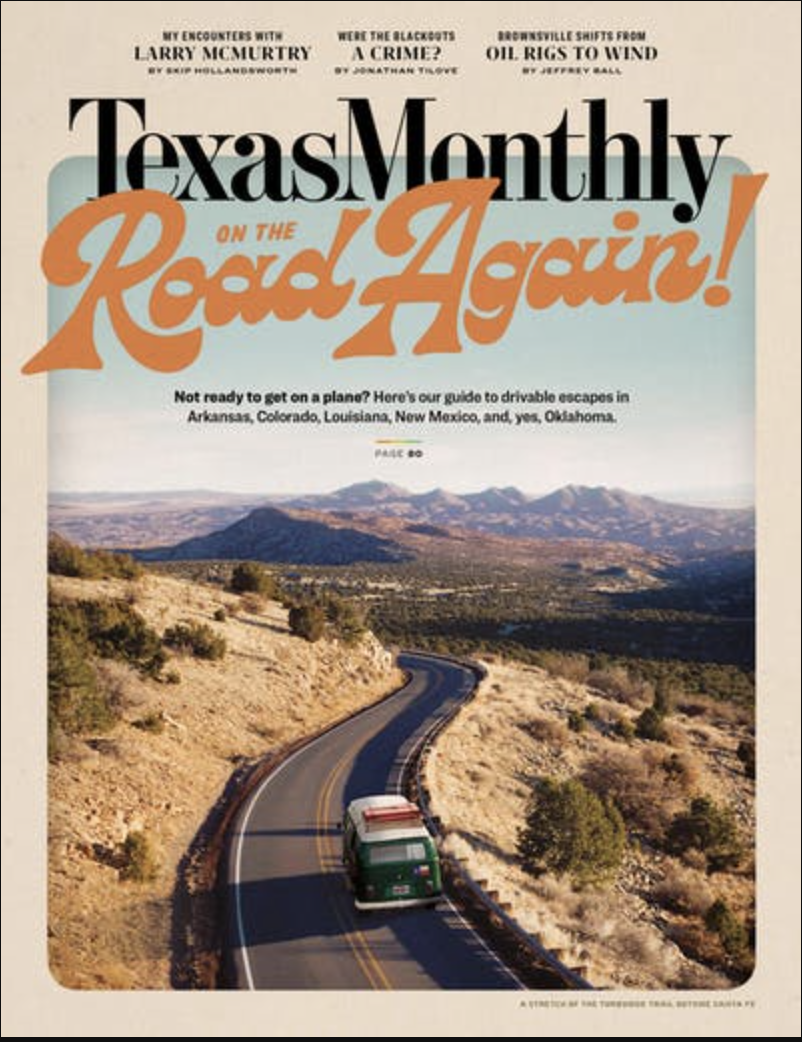

Sea Change | Texas Monthly | May 2021

Alongside the Brownsville Ship Channel, which shoots straight as a drill bit into the Gulf of Mexico, one of the biggest manufacturers of offshore oil rigs on the Gulf Coast turned 180 acres of dirt into a veritable gold mine. The shipyard there is a maze of 43 buildings, including 7 hangar-size assembly sheds in which welders’ sparks fly, pneumatic hammers pop, and signs warn in bold letters that any misstep could maim. Into one end of the factory slides sheet after three-ton sheet of steel. Out the other end, like intricate toys from some gargantuan Santa’s workshop, roll some of the heaviest and most sophisticated pieces of energy-industry machinery in the world.

During an extraordinary oil boom at the outset of the twenty-first century, the yard cranked out a steady stream of “jack-up rigs.” As tall as skyscrapers, these offshore platforms tap petroleum miles beneath the ocean floor and fetch about $250 million apiece. Five years ago the yard birthed a 21-story-tall beast called the Krechet, then the largest-ever land-based oil-drilling rig. But the Krechet—Russian for “gyrfalcon,” the largest falcon species and a predator of the Arctic tundra—has proved something of a dinosaur. Now pulling up oil for Irving-based ExxonMobil and its partners in Sakhalin, an island off Russia, it’s likely the last such oil rig the shipyard will ever build.

Today, in a pivot that reflects an oil-and-gas industry transformation sweeping Texas and the globe, the Brownsville yard’s workers are fabricating a new sort of ship. Like the old-style oil rigs, this offshore-energy vessel will head out to sea, lower its hulking steel legs onto the ocean floor, jack itself up on those haunches until it straddles the water’s choppy surface, and, in a dance of power and precision, drop into the murky depths machinery that will penetrate the subsea rock. This time, though, the natural resource the ship seeks to exploit isn’t oil. It’s wind.

Read more here.

The 'Mother Fracker' Reckons With the Mother of All Oil Busts | Texas Monthly | June 2020

One morning in mid-April, Scott Sheffield, the chief executive of Pioneer Natural Resources, one of the largest oil producers in America, seated himself in the wood-paneled boardroom of his company’s headquarters in Irving, gazed into his computer’s camera, and begged a trio of Texas politicians for a lifeline. Over the past two months, oil prices had tanked 60 percent, effectively ending a years-long Texas boom and heralding what many in the industry were calling “the mother of all busts.” As an estimated 30,000 viewers around the world watched online, Sheffield beseeched the three members of the Texas Railroad Commission, the elected body that regulates the state’s oil industry, to limit production, in a bid he hoped would ultimately boost the global price of crude.

Sheffield’s message bordered on heresy. He declared that the same oil revolution that had transformed the United States from petroleum importer to exporter had brought the industry to the brink of financial ruin. “It has been an economic disaster, especially the last ten years,” he said in testimony that had the feel of a key witness turning state’s evidence. “Nobody wants to give us capital because we have all destroyed capital and created economic waste.” If the government didn’t swoop in to save Texas oil producers from their excesses, Sheffield warned, “we will disappear as an industry, like the coal industry.”

It was a stunning admission coming from a man who has done as much as anyone to engineer a geological and geopolitical bonanza, one that now looks like a bubble. But the request for government intervention was also a characteristically strategic play for self-preservation by one of the longest-serving chieftains of the oil business—an industry that, following decades of expansion, now appears on the cusp of a slow, long-term decline.

With a love of the limelight, a flair for the dramatic, and an instinct for the jugular, Sheffield, a 68-year-old native of Dallas, has had a hand in the Texas oil sector’s every major swing over the past 45 years: a surge during the oil shocks of the seventies, a falloff throughout the eighties and nineties, and a renaissance starting in the early years of this century as the world sought massively more oil products and Texas unleashed new drilling and fracking technologies to serve up those hydrocarbons. Today, as the oil industry contracts, Sheffield is at the vanguard of a fight for market share, and for survival.

Sheffield took a modest family firm and ballooned it into a publicly traded behemoth—one that, before this spring’s crash, was valued at $26 billion. He did it by pursuing a straightforward strategy: drill, baby, drill. Through Republican and Democratic presidencies, in peace and in war, and to the general delight of investors, Sheffield’s Pioneer pumped up its stock by pumping ever more West Texas crude. Blessed by profitable acreage that Pioneer and its corporate predecessor locked down decades ago, when few others wanted it, and aided by aggressive lobbying in Austin and Washington, D.C., Pioneer grew to become the top driller in the Permian Basin and one of the biggest exploration and production companies in the country. By 2019, the Permian accounted for almost 40 percent of U.S. oil production and fully 5 percent of the global total—an amount nearly equal to the output of Iraq, the world’s sixth-largest producer.

But the Texas boom paralleled other seismic shifts in the international energy market—developments that pose an existential threat to petroleum. Global oil-demand growth has been slowing, and investor concerns over the environmental costs of burning fossil fuels have been increasing. These twin trends have prompted a broadening consensus, even among industry veterans, that oil’s best days are numbered. Yet until recently, Pioneer and most other Texas producers kept cranking out more and more oil—partying like it was 2005.

Now the party’s over. The Texas oil patch and the global energy markets were knocked down this spring by what Sheffield called a “double black swan” event: the simultaneous arrival of a pandemic, which slashed global demand, and a market-share fight between petroleum giants Russia and Saudi Arabia, which flooded more oil into that cratering market. But sober-minded industry insiders see that downturn as far more than another cyclical swoon. They view it as hastening a structural shriveling and consolidation that was already underway—a contraction likely to continue even though oil prices, starting in late April, began to recover. The energy sector’s share of the Standard & Poor’s 500, a key stock index, has tumbled from 29 percent in 1980 to 3 percent as of early June. “The era of rapid growth isn’t going to come back anytime soon”—and probably not at all, said Bob Brackett, a former oil-company executive and now an analyst at asset management firm Sanford Bernstein. “Industries sometimes behave in odd ways as they move toward senescence.”

Read more here.

Why the Coronavirus Could Make Big Oil Greener | Fortune | May 2020

In March, French President Emmanuel Macron went on national television from the Élysée Palace and told his countrymen that in the fight against the coronavirus, “We are at war.” Three days later, Patrick Pouyanné, chief executive of French oil giant Total, delivered to his roughly 100,000 employees a video message about the energy rout that was no less blunt. The price of oil had collapsed, “halving our share price,” noted the visibly pale CEO, speaking from the Total Tower in Paris into a microphone he was clutching in his right hand, in the style of a talk-show life coach. To stanch the bleeding, Total for 2020 would slash its capital spending more than 20%, nearly triple its planned cuts in operating expenses, and suspend share buybacks.

But one thing Total would not do, Pouyanné told his workers, was cut spending on its “new energies” division, a unit that includes investments in solar, wind, and batteries. That unit, Pouyanné declared, “will be safeguarded, as we must prepare for the future.” The upshot: This year, the approximately $2 billion Total will spend on its renewable-energy and energy-storage forays will account for about 13% of the company’s capital spending—a share that once would have been all but inconceivable for a fossil-fuel producer.

Long before this spring’s epic oil-price crash, the energy sector was struggling with a longer-term existential threat. Gone were the good old days, when oil consumption grew inexorably and the nations and corporations that controlled the most juice minted the juiciest profits. A scary new world had arrived, one in which oil demand was projected to peak in the next couple of decades even as external pressure surged—not just from environmental activists and regulators, but also from central banks and hedge funds—for Big Oil to diversify into lower-carbon energy sources.

That pressure already had begun to reshape the industry’s business strategy. Today’s energy-market carnage shows every sign of intensifying that low-carbon shift.

Read more here.

Big Oil's Hail Mary | Fortune | April 2020

Like an old racehorse, the West Seminole oilfield, a 12-square-mile patch of dirt on Texas’s far western flank, has been trudging along for years, kept kicking by an elixir its jockey shoots into its rump.

On a recent afternoon, as storm clouds blanketed the field and a winter wind howled, dozens of rusty pump jacks rocked up and down, groaning with each revolution as they sucked out more black gold. The drug that the field’s operator, Occidental Petroleum, injects into West Seminole loosens the oil in the stone beneath the sagebrush—forcing from the rock ever more of the hydrocarbon treasure locked inside its geologic pores. The magic medicine is an old industrial gas with a new image problem: carbon dioxide.

For decades, Occidental has been pumping massive quantities of CO₂ into the ground, juicing the flow of oil in aging fields that have lost the oomph nature originally gave them. The CO₂ frees more oil to rise to the surface, where it can be sold and burned. The petroleum industry has used this turbocharging technique—called “enhanced oil recovery”—elsewhere. But Houston-based Occidental is a global expert. Across thousands of square miles of eastern New Mexico and western Texas, on the iconic swath of land called the Permian Basin, the company nicknamed Oxy has built a multibillion-dollar web of infrastructure to manage vast quantities of the CO₂. The Permian rocks’ structure makes them particularly giving of their oil when their spongelike holes are coaxed with the greenhouse gas in liquid-like form.

Now, amid rising consumer anger about global warming and ballooning government subsidies for companies working to solve it, Oxy is attempting a stunning CO₂ pivot. It hopes to stop pumping into its fields CO₂ extracted from the earth, and instead deploy CO₂ sucked from man-made sources: from power plants, factories, and even thin air.

The company’s ambition is to build into a core business a process that has long been little more than a science project: “carbon capture and storage,” or CCS. It involves chemically snagging CO₂, typically as it’s wafting out of smokestacks but also from ambient air itself, and then injecting it into subterranean rocks. The goal: Rather than continue to dump CO₂ into the atmosphere, where it’s thickening a chemical blanket that’s warming the earth, humanity can bury it underground, ostensibly forever.

Countless difficulties imperil the CCS dream. Influential environmentalists oppose it, arguing it diverts attention from renewable energy. Beyond principle, technical dilemmas loom. One, now fueling a technological race, is how to slash the cost of capturing CO₂, which remains too expensive to work without subsidy. Another, now evolving into a high-stakes lobbying fight, is how far regulators should go in forcing oil companies to prove that CO₂ they’re sending into rock stays safely where it’s put.

Read more here.

Racing a Rising Tide | Fortune | November 2019

On a radiant summer day, all looks precisely right on the shore of Switzerland’s Lake Zurich, at the headquarters of global insurance behemoth Swiss Re. The postcard-perfect harbor bustles with bronzed sunbathers, dark-hulled yachts, and picnickers sipping wine. On the street alongside it, cyclists dutifully ring their handlebar bells for pedestrians, and blue-and-white city trams run on time. Inside the headquarters itself—a complex comprising a 1913 neobaroque edifice and a 2017 addition sheathed in undulating glass—art worth millions adorns white walls, coffee bars accented in leather and steel dispense mineral water in three levels of carbonation, and the employee cafeteria serves up chilled melon soup with mint, organic tofu with mango chutney, and fruit tarts and ice cream.

Yet things are anything but placid for Swiss Re, the 155-year-old corporation that, as measured by the $36.4 billion in revenue it collected from premiums in 2018, is the world’s largest “reinsurance” company. Executives anxiously are weighing the insurer’s financial exposure to some of its biggest clients. Ph.D. scientists are poring over algorithms to figure out how to cope with ballooning costs. Under intensifying pressure, they’re questioning much of what they know about assessing risk—and making decisions that could redirect billions of dollars.

Little known but crucial to commerce, reinsurers act as backstops of the global economy. They insure major multinationals, huge industrial facilities, and vast portfolios of risk that first-line insurance companies decide they need to hedge. That makes them leading indicators of the condition of capitalism—sprawling enterprises paid to ferret out and manage emerging mega-threats. Today, the threat that particularly worries Swiss Re is one that, like essentially every other company on the planet, it hasn’t figured out how to accurately quantify, let alone to combat: climate change.

For the insurance industry, global warming has advanced from a future ecological challenge to a present financial shock. Together, total losses to the economy from natural catastrophes and “man-made disasters” reached $165 billion in 2018; that followed a 2017 that, at $350 billion, cost more than twice as much. As a result, according to the Swiss Re Institute, the company’s research arm, 2017 and 2018 were for insurers the most-expensive two-year period of such catastrophes on record, requiring them to fork over $219 billion globally in checks. The majority of the insurers’ 2018 payouts were in North America, triggered by wildfires, thunderstorms, and hurricanes. The economic impact from catastrophes in 2018 alone was “shocking,” Christian Mumenthaler, Swiss Re’s chief executive, told shareholders this past March, in the company’s 2018 annual report. And Swiss Re is convinced, Mumenthaler made clear, that the trend is linked to rising temperatures: “What we’ve experienced over the past year must serve as a wake-up call to stand together in unity and step up our efforts against climate change.”

Read more here.

Electric Car Gold Rush | Fortune | September 2019

In a drab industrial zone of western Shanghai, amid factories that each year crank out hundreds of thousands of gasoline-powered cars, transmissions, and engines, the world’s largest automaker is racing to finish a new sort of plant, one that will produce a car unlike any it has made before. The 74-acre facility will have a newfangled assembly-line conveyor belt made of plastic instead of the typical steel or wood—a system that should be cheaper to reconfigure on the fly in order to manufacture cars whose shapes and layouts are likely to change more frequently and radically than any model the company has previously built. And the plant will be decked out with infrared cameras to monitor the safety of stockpiles of a component the company hasn’t before had to deal with in large volume: enormous batteries—each nearly as big as two coffins side by side—that have a nagging propensity to ignite.

What’s happening here in Shanghai is no incremental industrial tweak. It’s Volkswagen AG’s bet-the-corporation bid for supremacy in the electric-car age. “Volkswagen” translates as “the people’s car,” and for much of the eight decades of VW’s existence, the people were understood to be European or American and the cars to run on petroleum. But now VW’s biggest market is China, and the company, squeezed by new environmental mandates, has resolved to remake itself largely as a producer of electric vehicles, or EVs. Which makes this new Shanghai plant the forward base in the fight of VW’s life. When it starts producing electric vehicles next year, it will be VW’s “most modern factory worldwide,” says Fred Schulze, who heads production in Shanghai for VW’s joint venture in China with SAIC Motor, the Shanghai-based firm that is China’s biggest state-owned automaker. Schulze, a VW veteran, previously oversaw production of sport-utility and crossover vehicles from VW’s Audi unit—mostly gas-guzzlers such as the Q7 and Q8 but also the electric E-tron. From now on, Schulze says of VW, “our growth should be from EV cars.”

All across the global economy, titans of the fossil-fuel era are scrambling to adapt to an existential shift: the soaring economic viability of clean alternatives to dirty energy. Electricity and oil producers are struggling to ride—rather than be crushed by—a renewable-energy wave. Banks are trying to shore up their portfolios against losses induced by climate change. Automakers, though, are at a particularly scary fork in the road. The rise of electric vehicles—machines with multiple small motors instead of one big engine; with batteries instead of a fuel tank; with unprecedentedly extensive software systems instead of a transmission—is poised to redefine car making. If established automakers don’t adapt, and fast, the corporate infrastructure they have long seen as a signature asset may prove instead an insupportable stranded cost.

It’s far too soon to declare the end of the internal-combustion era. In the six months ended June 30, according to Wood Mackenzie, an energy-data firm, 97% of all new passenger cars sold globally had only an oil-burning engine under the hood. But it’s not too early to see that electric cars are coming on fast. Indeed, sales are shooting up beyond many supposed experts’ wildest projections. Globally, according to Wood Mackenzie, combined sales of passenger EVs—including full-electric vehicles, which have no combustion engine, and “plug-in hybrid-electric” vehicles, which augment their battery system with a combustion engine—jumped 47% from the first half of 2018 to the first half of 2019, to 1.1 million. The surge is being driven by a combination of factors: declining cost and improving technology, notably for batteries; increasingly convenient electric-charging infrastructure, particularly in large cities; and hefty government support.

Read more here.

Build. Burn. Repeat. | Mother Jones | September/October 2019

Standing on Shingletown Ridge and gazing west toward the setting sun, Bruce Miller eyes a rainbow of colors. He sees pink: the dusky sky blanketing a postcard-perfect valley 3,000 feet below. He sees gray: distant snow-capped mountains. He sees brown: century-old pine and oak trunks towering more than 100 feet above him. And he sees green: the profit he hopes to make by turning this 274-acre patch of forest into a subdivision for buyers looking for jaw-dropping views.

“This would be your high-dollar lot here,” the hearty 68-year-old tells me, halting our hike through a tangle of manzanita and poison oak to unfurl a map and point out the boundaries of a future home site. A sheer drop at the property’s rear reveals a stunning panorama. It also invites flames. “Fire,” Miller says, “burns uphill.”

Wildfire’s lethal tendency to surge up slopes was driven home last summer, when an inferno called the Carr Fire ripped through Shasta County, a chunk of Northern California pocked by crests and canyons as gorgeous as they are combustible. Lit by a spark from the wheel rim of a flat tire scraping the ground, the fire raged for 39 days, destroying more than 1,000 homes, killing eight people, and requiring some 3,500 firefighters from around the world and more than a dozen planes dropping chemicals to finally quell it. In November came the Camp Fire, which incinerated the nearby town of Paradise, killing 85 people. Together, the fires caused at least $18 billion in damage; bankrupted California’s largest utility, Pacific Gas and Electric; and forced the liquidation of at least one insurer. For weeks, Northern Californians breathed smoky air.

The destruction ended any delusion that humans could keep Mother Nature in check. They were harbingers of a new kind of megafire being unleashed on a warming world.

Read more here.

The Race to Build a Better Battery | Fortune | June 2019

At first glance, all seems serene on a spring morning at the research-and-development campus of SK Innovation, one of Korea’s biggest industrial conglomerates. The campus sits in Daejeon, a tidy, planned city an hour’s high-speed-train ride south of Seoul that the national government has built up as a technology hub. Dotting SK’s rolling acres are tastefully modern glass-and-steel buildings that wouldn’t be out of place in a glossy architecture magazine. One contains a library, its tables stocked with rolls of butcher paper and Post-it notes to spur creativity. Another houses an espresso bar where engineers queue for caffeination. A cool breeze blows. Birds chirp. Pink cherry blossoms bloom.

Then Jaeyoun Hwang, who directs business strategy for SK’s R&D operation, steers the Kia electric car in which he is driving me around the campus to a stop at the top of a hill. In front of us looms K-8, a seven-story-tall cube of a building sheathed in matte silver siding and devoid of any visible windows. Its only discernible marking is, at the top corner of one wall, a stylized orange outline of a familiar object: a battery. K-8 appears whimsical, almost a bauble, until Hwang explains that four other buildings on the campus, plus another one under construction, also are for battery research—an activity at SK that employs several hundred people and counting. When I ask to go inside K-8 for a look, Hwang says it’s out of the question. When I raise my camera to take a picture, he stops me. “In this area,” he says, “photographs of the buildings are prohibited.”

SK has a sprawling R&D campus because it has a storied technological pedigree—as Korea’s oldest oil refiner. Now the petrochemical company is hitching its future to electric cars. It has inked deals to make batteries for some of the world’s largest automakers, notably Volkswagen AG, which, following a crippling scandal in which it was found to have deliberately and repeatedly violated pollution rules in producing its diesel vehicles, has pledged a green corporate rebirth, shifting much of its lineup to cars that run on electricity rather than oil. SK has made huge deals with VW and other automakers, including Daimler AG, which says it will sell 10 pure-electric car models by 2022, and Beijing Automotive Group, or BAIC Group, China’s largest maker of pure-electric cars. SK is racing to build massive battery plants in China, Europe, and the United States, including one an hour’s drive from Atlanta. It is moving by 2025 to balloon its battery production, mulling investing some $10 billion in the effort over that span. That’s a serious number even for a behemoth that in its various corporate incarnations, has spent more than a half-century processing black gold sucked from the ground. “These days,” Hwang says of SK’s battery business, “the order volume is huge.”

For years, the race to build a better battery was contained to consumer electronics. It was a growing business, but it wasn’t going to reorder capitalism. Now, amid an onslaught of electric cars on the road and renewable electricity on the power grid, the race is gearing up into a corporate and geopolitical death match. It suddenly has the dead-serious attention of many of the planet’s biggest multinationals, particularly auto giants, oil majors, and power producers. Having historically dismissed affordable energy storage as a pipe dream, they now view it as an existential threat—one that, if they don’t harness it, could disintermediate them. It also divides the world’s major economic powers, which see dominance of energy storage in the 21st century as akin to control of coal in the 19th century and of oil in the 20th. One clear sign: Battery-technology competition is deeply woven into the ongoing trade tensions between the U.S. and China.

Read more here.

Sun Blocked | Mother Jones | July/August 2018

The headquarters of Huawei Technologies, the world’s largest maker of telecommunications equipment, sprawls across two square miles in the global manufacturing megalopolis of Shenzhen, China. At the center of its campus, surrounded by hulking office buildings of red brick and gray stone, sits a meticulously landscaped artificial pond. On the day I visited, two black swans glided across the water—fitting omens for the trajectory of Chinese technological power.

Most Americans have never heard of Huawei (pronounced HWA-way), but the company operates in 170 countries, employs 180,000 people, and in 2017 had revenue of $92 billion. These days it’s leveraging its telecom experience to corner what it sees as the next big thing: solar energy. The company’s main solar product is a suitcase-sized device called an inverter, which changes the direct current, or DC, that a solar panel produces into the type that can be fed into a power grid: alternating current, or AC.

Huawei is boosting its solar-inverter business not just by undercutting Western companies on price, but by beating them on innovation. Though inverters have been around for more than a century, many of the features Huawei offers are new, designed to improve the reliability of remote solar farms. A passive cooling system dissipates heat more reliably than fans, which are prone to breakage. And communications technology allows technicians to diagnose problems remotely, so they don’t have to venture into the field. Huawei is the top supplier of solar inverters globally, commanding 20 percent of the world market. With 800 solar-inverter engineers in research-and-development centers spanning China, Europe, and the United States, Huawei, which translates from Mandarin as “Chinese achievement,” presents a glimpse at the clean-energy juggernaut that is today’s China. In 2017, Huawei spent $13.8 billion on R&D. That amounted to 15 percent of its revenue—a higher portion than at Apple, Samsung, or Microsoft.

“Even though Western countries have some misunderstanding that we don’t innovate, we are confident,” Zhang Feng, the company’s head of solar-inverter R&D, told me. Yang Longjuan, the spokeswoman dispatched to shepherd me during my Shenzhen visit, put it more bluntly. “It’s like the Qing dynasty. You have to be careful,” she said, comparing the West today to the Chinese empire that lost power in 1912, a downfall historians ascribe in part to hubris. Any lingering Western belief that China doesn’t innovate “is the old impression of China,” Yang added, sitting in the back seat of a black Audi and thumbing between two smartphones as a Huawei driver sped us past the company’s Shenzhen offices and factories. “China is changing very fast.”

“Made in China” has long been seen as shorthand for shoddy. Whether it was fast fashion or toys, the rap on Chinese manufacturing used to be that it was all about leveraging cut-rate labor to knock off products designed in the West. Cheaper, certainly. Better, hardly. But that is changing fast—especially in the booming clean-energy sector. From solar to batteries to electric vehicles, China is rapidly gaining on the West in the most important arena of all: innovation.

Read more here.

Why Carbon Pricing Isn't Working | Foreign Affairs | July/August 2018

For decades, as the reality of climate change has set in, policymakers have pushed for an elegant solution: carbon pricing, a system that forces polluters to pay when they emit carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. Among the places that have imposed or scheduled it are Canada, China, South Korea, the EU, and about a dozen U.S. states. Much as a town charges people for every pound of trash tossed into its dump, these jurisdictions are charging polluters for every ton of carbon coughed into the global atmosphere, thus encouraging the dirty to go clean.

In theory, a price on carbon makes sense. It incentivizes a shift to low-carbon technologies and lets the market decide which ones will generate the biggest environmental bang for the buck. Because the system harnesses the market to help the planet, it has garnered endorsements across the political spectrum. Its adherents include Greenpeace and ExxonMobil, leftist Democrats and conservative Republicans, rich nations and poor nations, Silicon Valley and the Rust Belt. Essentially every major multilateral institution endorses carbon pricing: the International Monetary Fund, the UN, and the World Bank, to name a few. Christine Lagarde, the managing director of the IMF, spoke for many in 2017 when she recommended a simple approach to dealing with carbon dioxide: “Price it right, tax it smart, do it now.”

In practice, however, there’s a problem with the idea of slashing carbon emissions by putting a price on them: it isn’t doing much about climate change. More governments than ever are imposing prices on carbon, even as U.S. President Donald Trump backpedals on efforts to combat global warming, yet more carbon than ever is wafting up into the air. Last year, the world’s energy-related greenhouse gas output, which had been flat for three years, rose to an all-time high. Absent effective new policies, the International Energy Agency has projected, energy-related greenhouse gas emissions will continue rising through at least 2040.

If governments proved willing to impose carbon prices that were sufficiently high and affected a broad enough swath of the economy, those prices could make a real environmental difference. But political concerns have kept governments from doing so, resulting in carbon prices that are too low and too narrowly applied to meaningfully curb emissions. The existing carbon-pricing schemes tend to squeeze only certain sectors of the economy, leaving others essentially free to pollute. And even in those sectors in which carbon pricing might have a significant effect, policymakers have lacked the spine to impose a high enough price. The result is that a policy prescription widely billed as a panacea is acting as a narcotic. It’s giving politicians and the public the warm feeling that they’re fighting climate change even as the problem continues to grow.

Read more here.

Lone Star Rising | Fortune | June 2018

Smack in the middle of Grier Brunson’s family’s ranch, a patch of West Texas dirt that sprawls across 45 square miles, sits a lush, green dip in the land that the family calls “the draw.”

Thousands of years ago, Pueblos built rocky settlements here. Hundreds of years ago, Comanches thundered on horseback across this plain. Today, the natural bounty in and around the draw is producing a rather more modern stampede.

On the rim of the draw, amid the mesquite trees and the sagebrush, oil rigs loom like rockets at launch, and a team fracking a well shoots untold thousands of gallons of water and hundreds of truckloads of sand down into the earth, using huge hydraulic pumps that emit a dull, constant roar. For the Brunson family, these are the sights and sounds of money: Two miles underground, oil—thousands of barrels of it every day, worth millions of dollars—is being cracked loose from the rock and pulled up through carefully engineered holes.

Under the terms of the mineral leases they’ve signed with oil companies, Brunson and his extended family receive one-quarter of the revenue from every barrel the drilling companies pull up. The Brunsons have about 50 wells on the ranch, of various sizes and ages. With oil trading around $70 per barrel, among the most prolific of those wells could generate as much as $3.8 million per year in royalties before taxes for the Brunsons. And that’s just for the oil. The Brunsons earn additional royalties from the sale of the natural gas and other hydrocarbons that come up with the oil. And they earn fees from the drilling companies for permission to install infrastructure such as pipelines.

The size of this unexpected windfall is a bit bizarre and more than a little embarrassing to Brunson, who drives a GMC pickup, idolizes a grandfather who rustled cattle here nearly 100 years back, and curses like a cowboy—“goddamn it!”—when he drives across his ranch and sees what he regards as messy operations by the oil companies leasing his land. The money “is more than we need. We don’t know what to do with it. But it keeps coming,” says Brunson, a lanky, bespectacled 73-year-old, who evokes Colonel Sanders with his silver goatee and Will Rogers with his silver tongue.

“We have no inclination to be rich beyond our wildest dreams,” he adds. “Apparently, it’s going to happen anyway.”

Indeed, it’s hard not to rack up wealth when fate puts your ranch at the epicenter of one of the biggest oil booms in history. Brunson’s land sits in the bull’s-eye of the Permian Basin, a petroleum-rich swath of western Texas and southeastern New Mexico—bigger than North Dakota—that is experiencing a gusher of production growth epic even by the outsize standards of the Lone Star State. The boom is remaking every aspect of life in this parched part of the country, for good and for ill. And it is reverberating across the globe.

Read more here.

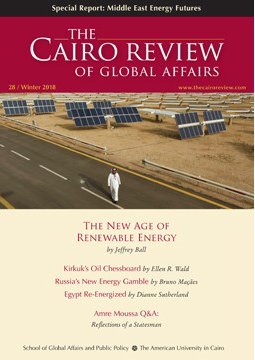

The New Age of Renewable Energy | The Cairo Review of Global Affairs | Winter 2018

Near the town of Sweihan, in southern Abu Dhabi, construction is underway on what is slated to be the world’s largest solar project, an expanse of metal and glass expected to cover three square miles. At Sakaka, in northern Saudi Arabia, plans are proceeding for a massive solar installation whose electricity appears likely to sell for less than 3 cents per kilowatt hour, one of the lowest prices in the world. Morocco, which has opened at the foot of the High Atlas mountains a solar project composed of hundreds of curved mirrors, each the size of a bus, says that within a decade the country will produce half its electricity from renewable sources.

Renewable energy is undergoing a revolution. It is surging in scale and plummeting in price, and in the process it is deepening geopolitical rifts, upending corporate business models, and reshaping global energy markets. No place illustrates renewable energy’s unexpected rise and unpredictable ripples better than the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), a region in which several countries that for a century have produced epic power with energy from the ground are now finding compelling economic reasons to exploit energy from the sky. It is a shift that would have been unthinkable just a decade ago.

Geologists, investors, and policy makers have known for generations that this sandy patch of the planet brimming with buried fossil fuel also is blessed with vast supplies of wind and sunlight. What is changing is that they now see compelling financial reasons to care. A confluence of economic forces that they either didn’t sense coming or hoped would sputter has power brokers in the MENA region gunning to exploit the money-making potential of a suite of energy sources previously dubbed alternative but now entering the mainstream.

The renewable-energy transformation, still in its early days, begs two questions.

One is economic: who—which countries, industries, and individual companies—will win and lose in the diversification from energy that’s finite to energy that’s not? Another is environmental: will the renewable-energy ramp-up prove big enough to meaningfully help a planet that as a result of human activity has been heating up?

The answers will depend largely on finance and policy—which thus far have been economically inefficient and will have to become vastly more productive if renewable energy is to reach its economic and environmental promise.

The dirty truth about renewable energy is that it isn’t yet making much of an environmental difference. Whether it ends up protecting the planet—whether, that is, it significantly curbs carbon emissions—will depend on whether its costs decline far more radically than they have thus far. As such, a ruthless focus on wringing out excess cost should be the goal of policymakers who want to optimize renewable-energy sources and meaningfully increase their role in the greater economy.

Read more here.

Germany's High-Priced Energy Revolution | Fortune | March 2017

By Jeffrey Ball

As many generations of Dieter Dürrmeier’s family as he can track have grown vegetables and tended livestock here in Opfingen, a hilly corner of southern Germany near the French and Swiss borders. Over the decades the Dürrmeiers have adapted, ever on the lookout for new ways to make money. In 1963, Dürrmeier’s father exploited cheap government loans to move his 136-acre farm from the crowded village to the outskirts of town. In 1986 the Dürrmeiers stopped raising cows and shifted to the less cyclical business of boarding wealthy city dwellers’ horses. But the family’s current shift has been its most lucrative yet. Though they still grow asparagus and grapes and tend to the equines, the Dürrmeiers today harvest their fattest earnings from sunshine. Thanks to generous checks from the German people, that crop from the sky spins off cash more reliably—and at higher margins—than anything the Dürrmeiers have ever grown in the ground.

On a recent frigid winter night, wearing a red-and-green flannel shirt and mud-caked boots, Dürrmeier takes a break from feeding the horses and chats under the eave of a barn, one of four work buildings on whose roofs he has installed subsidized solar panels. The glass-and-metal sheets, whose production he monitors in real time on a computer in his office, fetch him a steady profit of about 40,000 euros (about $42,000) annually. That equates to about 40% of the earnings from his entire farming operation. As he describes his solar windfall, the balding, barrel-chested 62-year-old is both proud and embarrassed.

“For us it’s a very good business, but for the German people it’s very bad,” Dürrmeier says of the government policy that has turned intermittent sunshine into an all but sure thing for his wallet. Germany’s solar-subsidy scheme pays him a set price for every kilowatt-hour of electricity he produces with his solar panels and sells into the grid. It guarantees him that price, which when he started was several times the prevailing electricity rate, for 20 years.

When he learned of the subsidy more than a decade ago, he says, “I was at first skeptical because it was a bit too good, and I personally objected because I thought that subsidies were generally bad for the economy as a whole. But if it was offered, I had to take it. It was against my beliefs, but as an entrepreneur it was the right thing to do.”

Germany has launched a renewable-energy revolution, and it’s paying a fortune to achieve it. In the past decade its green-minded politicians, backed by green-minded voters, have undertaken an extraordinary energy transition known in German as the Energiewende. At the center of the transformation has been a slate of renewable-energy subsidies that have dramatically scaled up once-niche solar and wind technologies and in the process have slashed their cost, making them competitive in some cases with fossil fuels.

Thanks to Germany’s lavish first-mover spending, a raft of second-mover countries, from the U.S. to China to India, are now installing solar and wind power on a huge scale. If renewable energy ends up significantly helping curb climate change, then history may judge the Energiewende as a remarkable example of global leadership.

The raw ambition of the Energiewende is both mind-boggling and quintessentially German. It reflects the engineering prowess of a country that built the Autobahn, pioneered modernist architecture, and cranks out sleek BMWs and Mercedes. It evokes the environmental ideals of a society that idolizes the Black Forest, led the way in organic farming, and still celebrates Goethe’s nature-loving poems. It bespeaks the moral confidence, both wrong and right, of a culture that created Romanticism in the late 18th century, Nazism in the 1930s, and one of the world’s most generous campaigns to welcome refugees today.

But all that ambition is bleeding Germany. The mounting costs are testing its resolve. Leading politicians, even those with strong environmental credibility, are racing to rein in spending. If they can’t achieve that, then Germany’s near miracle may be remembered as the environmental equivalent of, say, heart-transplant surgery: a worthy endeavor, undoubtedly, but one that remains unattainable for all but the very wealthiest.

Read the full piece here.

Why the Saudis Are Going Solar | The Atlantic | July/August 2015

By Jeffrey Ball

Prince Turki bin Saud bin Mohammad Al Saud belongs to the family that rules Saudi Arabia. He wears a white thawb and ghutra, the traditional robe and headdress of Arab men, and he has a cavernous office hung with portraits of three Saudi royals. When I visited him in Riyadh this spring, a waiter poured tea and subordinates took notes as Turki spoke. Everything about the man seemed to suggest Western notions of a complacent functionary in a complacent, oil-rich kingdom.

But Turki doesn’t fit the stereotype, and neither does his country. Quietly, the prince is helping Saudi Arabia—the quintessential petrostate—prepare to make what could be one of the world’s biggest investments in solar power.

Near Riyadh, the government is preparing to build a commercial-scale solar-panel factory. On the Persian Gulf coast, another factory is about to begin producing large quantities of polysilicon, a material used to make solar cells. And next year, the two state-owned companies that control the energy sector—Saudi Aramco, the world’s biggest oil company, and the Saudi Electricity Company, the kingdom’s main power producer—plan to jointly break ground on about 10 solar projects around the country.

Turki heads two Saudi entities that are pushing solar hard: the King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology, a national research-and-development agency based in Riyadh, and Taqnia, a state-owned company that has made several investments in renewable energy and is looking to make more. “We have a clear interest in solar energy,” Turki told me. “And it will soon be expanding exponentially in the kingdom.”

Such talk sounds revolutionary in Saudi Arabia, for decades a poster child for fossil-fuel waste. The government sells gasoline to consumers for about 50 cents a gallon and electricity for as little as 1 cent a kilowatt-hour, a fraction of the lowest prices in the United States. As a result, the highways buzz with Cadillacs, Lincolns, and monster SUVs; few buildings have insulation; and people keep their home air conditioners running—often at temperatures that require sweaters—even when they go on vacation.

Saudi Arabia produces much of its electricity by burning oil, a practice that most countries abandoned long ago, reasoning that they could use coal and natural gas instead and save oil for transportation, an application for which there is no mainstream alternative. Most of Saudi Arabia’s power plants are colossally inefficient, as are its air conditioners, which consumed 70 percent of the kingdom’s electricity in 2013. Although the kingdom has just 30 million people, it is the world’s sixth-largest consumer of oil.

Now, Saudi rulers say, things must change. Their motivation isn’t concern about global warming; the last thing they want is an end to the fossil-fuel era. Quite the contrary: they see investing in solar energy as a way to remain a global oil power.

Read the full story here.