The New Age of Renewable Energy | The Cairo Review of Global Affairs | Winter 2018

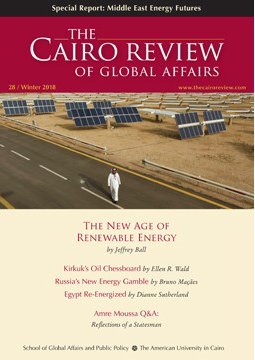

Near the town of Sweihan, in southern Abu Dhabi, construction is underway on what is slated to be the world’s largest solar project, an expanse of metal and glass expected to cover three square miles. At Sakaka, in northern Saudi Arabia, plans are proceeding for a massive solar installation whose electricity appears likely to sell for less than 3 cents per kilowatt hour, one of the lowest prices in the world. Morocco, which has opened at the foot of the High Atlas mountains a solar project composed of hundreds of curved mirrors, each the size of a bus, says that within a decade the country will produce half its electricity from renewable sources.

Renewable energy is undergoing a revolution. It is surging in scale and plummeting in price, and in the process it is deepening geopolitical rifts, upending corporate business models, and reshaping global energy markets. No place illustrates renewable energy’s unexpected rise and unpredictable ripples better than the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), a region in which several countries that for a century have produced epic power with energy from the ground are now finding compelling economic reasons to exploit energy from the sky. It is a shift that would have been unthinkable just a decade ago.

Geologists, investors, and policy makers have known for generations that this sandy patch of the planet brimming with buried fossil fuel also is blessed with vast supplies of wind and sunlight. What is changing is that they now see compelling financial reasons to care. A confluence of economic forces that they either didn’t sense coming or hoped would sputter has power brokers in the MENA region gunning to exploit the money-making potential of a suite of energy sources previously dubbed alternative but now entering the mainstream.

The renewable-energy transformation, still in its early days, begs two questions.

One is economic: who—which countries, industries, and individual companies—will win and lose in the diversification from energy that’s finite to energy that’s not? Another is environmental: will the renewable-energy ramp-up prove big enough to meaningfully help a planet that as a result of human activity has been heating up?

The answers will depend largely on finance and policy—which thus far have been economically inefficient and will have to become vastly more productive if renewable energy is to reach its economic and environmental promise.

The dirty truth about renewable energy is that it isn’t yet making much of an environmental difference. Whether it ends up protecting the planet—whether, that is, it significantly curbs carbon emissions—will depend on whether its costs decline far more radically than they have thus far. As such, a ruthless focus on wringing out excess cost should be the goal of policymakers who want to optimize renewable-energy sources and meaningfully increase their role in the greater economy.

Read more here.